| Title | International Migrations in Latin America and the Caribbean Edition Nº 65 May-August 2002 |

| Author: | Permanent Secretariat of SELA |

INTERNATIONAL MIGRATION IN LATIN AMERICA AND THE

CARIBBEAN:

SOCIAL DEMOGRAPHIC AND ECONOMIC TRAITS

Miguel

Villa and Jorge Martínez

(ECLAC / CELADE, Santiago,

Chile)

Introduction: The complexities of international

migration

International migration is one of the most

enduring social processes throughout history and its relevance underlines

new concerns riddled with perceptions that differ from observable reality.

It is important to point out that in the past the movement of people

played a starring role in economic, social and political transformations

as it complemented the expansion of trade and the world economy,

contributed to the creation of nations and territories, fuelled

urbanization and opened up new areas of production.

During the second

half of the 19th century and the first decades of the 20th century the

bulk of migration consisted of two major contrasting flows: one included

the free movement of Europeans who played a key role in the economic

convergence of some regions of the old and new world; the other consisted

of the movement of workers of diverse origin, mostly Asian, towards

tropical regions. This at times forced movement resulted in an expansion

of social and economic inequalities at the international level. These

flows, which were fuelled by different forces, opened up opportunities,

won the approval of the countries of destination and contributed

significantly to social and cultural changes (ECLAC, 2002).

In

today's world migration is the object of contrasting views and many of the

concerns it arises stem from perceptions on its inherently conflicting

aspects. This is particularly true in receiving countries where concerns

centre on the different types of illegal immigration, asylum requests,

immigrants' integration possibilities and the need to regulate the inflow

of workers. The acknowledgment of immigrants' economic and cultural

contributions - as a reflection of their entrepreneurial capacities - or

the evaluation of the consequences the current globalization phase will

have on migrations - such as the deepening of development's inequalities-

are issues seldom discussed. On the other hand, in the countries of

origin, which are mostly developing nations, it is felt that the "escape

valve" effect the emigration of workers has on the local labour market and

the remittances emigrants send from abroad are positive elements. Still,

these countries are also concerned with the loss of skilled human

resources and, in general, the risks of human rights abuses against

migrants, often fuelled by racist or xenophobic behaviour.

The

contrasting views on migration are but a sample of this phenomenon's

current complexities. Today's globalization is different in that States -

to ensure greater fluidity in the exchange of goods and stocks - surrender

part of their power to supra-national entities and acknowledge the primacy

of universal human rights instruments, but retain their exclusive rights

regarding regulations on the entry and permanence of foreigners in their

territories. This has led some authors to argue that migration is the grip

that knocks down sovereignty (Sassen, 2001). In a recent study ECLAC

pointed out that rather than a 'globalization of migrations' we are

witnessing today a paradox: globalization formally excludes international

migration. In a world more connected than ever before and at a time when

financial, information and trade flows are liberalized, the movement of

people faces restrictive barriers. This reveals that the asymmetries of a

limited globalization risk deepening inequalities in development levels

(ECLAC, 2002)1. The

persistence of these barriers - related to border control practices that

operate even between countries members of free trade agreements - causes

the proliferation of situations of illegal entry. For many immigrants

these situations result in lack of protection and

vulnerability.

Theoretically, international migration represents a

fundamental aspect of integration processes between nations that, by

definition, require the removal of barriers. Nevertheless, the movement of

people is not explicitly acknowledged in most integration arrangements.

This is particularly evident in the agreements that establish preferential

market areas, since they assume that trade flows compete with or

substitute the flow of workers. Only when integration comprises political

and social tenants that may allow for the development of communal areas -

the best example of which is the European Union - will it be possible to

establish common rules of the game regarding the movement of people (Di

Filippo, 2000; Hovy and Zlotnik, 1995; Martínez,

2002a).

I. International Migration in

Latin America and the Caribbean

International migration's

many relevant aspects render impossible an in depth examination of each

one. As Izquierdo points out (1996) in understanding this phenomenon,

images have been more effective than a thousand words, to the point of

obliterating evidence. Therefore, the need arises to draw a general

orientation map based on empirical records regarding the major tendencies

and patterns that may be observed in the region.

1. Major

Tendencies

Latin America and the Caribbean, traditionally a

region that attracted migrants, became a source of emigration during the

last decades and the number of countries of destination has progressively

increased. It is estimated that nearly 20 million Latin American and

Caribbean nationals - that is, over 13% of the 150 million migrants

throughout the world - live outside their countries of birth (IOM-United

Nations, 2000).2 Half of the region's emigrants emigrated during the 1990s, mostly

to the U.S. During the same period, new flows of emigrants - smaller but

increasing at unprecedented rates - entered European countries.

Intra-regional migration, which accompanied the different stages of Latin

American and Caribbean countries development, retains some of its

traditional traits but has decreased due partly to the lesser

attractiveness of the major countries of destination (Argentina and

Venezuela) (ECLAC, 2002).

Keeping in mind the limited up to date

information available on migration, three major migration patterns can be

said to have prevailed in the region during the second half of the 20th

century (Villa and Martínez, 2000 and 2001). The first concerns

immigration from overseas, particularly the Old World. The second, deeply

rooted in the region's history and previous to the establishment of

boundaries, resulted from the exchange of people within the countries of

the region. Finally, the third migration pattern refers to emigration to

countries outside Latin America and the Caribbean. The growing intensity

of these later flows begins to show signs of expulsion. Even though these

three patterns coexist the quantitative importance of each has changed

throughout time.

2. A Region with an Immigration

Past

Between the second half of the 19th century and the first

of the 20th century the flow of immigrants from overseas countries was

significant in several countries, even though it fluctuated throughout

time. It played a decisive role, both in quantitative and qualitative

terms, in the configuration of national societies, particularly in

countries on the Atlantic coast, which offered favourable conditions for

the social and economic insertion of migrants, mostly form Southern Europe

and, to a lesser extent, the Near East and Asia. European immigration was

particularly strong in the areas more integrated to the international

economy that, besides possessing "empty spaces", experienced an

accelerated process of modernization. This economic expansion created jobs

offering better salaries than those prevailing in Southern European

countries, a fact that stimulated immigration and insured upward mobility.

Of the 11 million Europeans -38% Italians, 28% Spanish and 11% Portuguese-

who entered the region, half settled in Argentina and more than one third

in Brazil (Pellegrino 2001),

Following World War II Europe

experienced a vigorous economic transformation, which began in the

countries of the North and the West and later spread through integration

channels to the countries in the South. This motivated people to remain in

their country of origin. At the same time, the gap between the social and

economic development of European and Latin American and Caribbean

countries widened. Both factors resulted in a considerable decrease in

migration flows to this region and stimulated the return of migrants to

the old continent. Due to the lack of new immigration flows the European

immigration stock continued to age and this, together with mortality (and

returning migrants) led to a progressive decrease of such stock. The total

number of immigrants from overseas countries fell from almost four million

in the 1970 census to less than 2.5 million in 1990.

Even though

immigration from overseas countries has not ceased entirely -some smaller

flows are still entering the region, mostly from Asia- it has declined

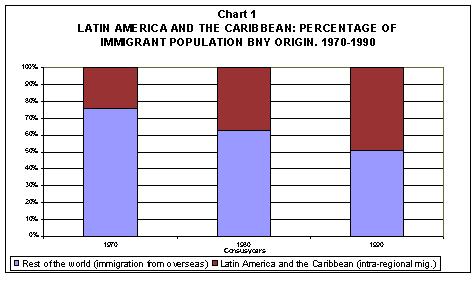

during the last decades. The percentage of people from countries outside

the region within the stock of immigrants censed in Latin American

countries fell from representing three-fourths of the total in 1970 to a

little over half in 1990 (Chart 1). This evolution clearly indicates that

during the third part of the 20th century Latin America lost its

traditional attractiveness for people from other regions. Still, it must

be stressed that only some countries of the region held such

attractiveness, as demonstrated by the fact that 80% of the stock of

immigrants from outside the region that was censed in 1990 were from

Argentina, Brazil and Venezuela. Other countries such as Uruguay, Cuba,

Chile and Mexico also received sizable flows of European

immigrants.3

Source: IMILA

Project,

CELADE.

3. The Sizable Exchange of Population

between

Countries of the Region

The movement of people

across national boundaries is deeply rooted in the social and economic

history of Latin American and Caribbean territories. Geographical and

cultural proximity facilitated these movements that until the early 1990s

were destined mostly to countries with more favourable labour conditions

and higher levels of social equality. This type of migration flows

responds to structural factors and is sensitive to situations of economic

expansion or contraction and social and political developments

(Pellegrino, 2001 and 1995). The abandonment or re- establishment of

democratic forms of government has particularly caused waves of immigrants

and "returns" between neighbouring countries. The decrease in the number

of immigrants from overseas and the increase in the so-called border

migration and economic integration efforts have led to a growing interest

in the study of intra-regional migration flows. Some of these movements,

closely linked to the articulation of labour markets between neighbouring

countries, represent virtual extensions of intra-national

migration.

During the 1970s intra-Latin American migration grew

considerably. Due to the persistence of structural factors and social and

political alterations the number of migrants tripled, reaching close to

two million in 1980 (Chart 1). On the other hand, during the eighties this

stock of immigrants registered a more modest increase as a result of the

economic crisis and the structural reforms programs that followed it

-which were felt particularly in the major countries of destination- and

of the re-establishment of civil cohabitation norms in several countries.

During that period the cumulative total of such immigrants increased to

just 2.2 million. Even though this suggests the relative stabilization of

the absolute number of intra-Latin America migrants, movements continued

to occur, this time mostly as returns to the country of origin. Moreover,

it is possible that part of traditional migration was replaced by new

types of movements, such as temporary moves that do not imply a change of

residence, as a result of the longer life-span of a growing number of the

population, a phenomenon that coincided with the region economies' new

territorial structures and more flexible labour mechanisms.

In

spite of the changes in the social, economic and political context, the

origin and destination of migration flows within Latin America did not

alter greatly between 1970 and 1990, thus revealing a consolidation of the

region's migratory map. Thus, in 1990 almost two-thirds of the Latin

Americans who resided in countries of the region other than their own

lived in Argentina and Venezuela.

Argentina has been the

traditional destination for many Paraguayans, Chileans, Bolivians and

Uruguayans who were lured by the availability of jobs in agriculture,

manufacturing, construction and services. As European immigration

decreased their presence became more noticeable. During the 1970s

Venezuela's economy, stimulated by the oil boom, attracted mostly

Colombians and people from the Southern Cone countries who were forced to

leave their homes.

Throughout the so-called lost decade of the

1980's immigration flows to Argentina and Venezuela decreased

considerably: data from the 1990s censuses reveal a reduction in the total

stock of immigrants in both countries. However, through indirect estimates

we can conclude that during those years both received considerable numbers

of immigrants from neighbouring countries.4

During the same period, some nations that traditionally had

been sources of emigration registered a significant return migration.

During the 1970s Paraguay's economic expansion spurred by vast

hydroelectric projects and by an intense colonization process stimulated

the return of Paraguayans who had settled in Argentina and immigration

from neighbouring countries, particularly Brazil. Since the mid-1990s

Chile has been receiving return migrants as well as large numbers of

immigrants from other Latin American countries, particularly Peru (CEDLA

and others, 2000; Martínez, 1997), Argentina and Ecuador. The effects of

recent economic crises, which imply a possible alteration of the

intra-regional migrations' map, will only be ascertained once the results

of the censuses of the 2000-decade are made available.

In Central

America, the serious social and political alterations of the 1970s and

1980s, together with development's traditional structural shortcomings,

caused a massive emigration. Thus, between 1973 and 1984 the stock of

Nicaraguan and Salvadorian immigrants in Costa Rica increased

considerably. This tendency continued during the following years: the

Costa Rican census for the year 2000 reveals a total of 300,000 immigrants

-which represent 8% of the country's total population- of which 75% are

from Nicaragua. The number of Nicaraguan immigrants to Costa Rica

quintupled in just sixteen years (INEC, 2001). Mexico has also been a

major destination for emigrants from Central America, mostly Guatemala and

El Salvador. A similar situation occurred with Belize, whose number of

immigrants was less large but had vast demographic, social and cultural

consequences. Still, the peace agreements signed by the major social

actors in Central American countries appear to have contributed to the

re-insertion of groups that had sought asylum and refuge in Mexico. Data

from the 2000 census in Mexico indicate that the number of immigrants from

Guatemala has decreased substantially. The repatriation of these

immigrants was not without difficulties as often it occurred precipitously

and some people were not able to settle again in their countries of origin

(Castillo, 1999).

Transit movements through Mexico, Belize and

Guatemala, on the way to the U.S., are another aspect of Central American

migration. The seasonal displacement of labour has a long and relevant

tradition in these countries, as is demonstrated by the flow of Guatemalan

workers who move periodically to the Soconusco region in Mexico's Chiapas

State (Castillo, 1990).

Within the whole intra-regional Latin

American emigrant population in 1990, Colombians were the most numerous:

over 600,000 were censed in the censuses of other Latin American countries

(90% in Venezuela). Chileans and Paraguayans held the second place, with a

total of close to 280,000 emigrants (three-fourths censed in Argentina).

In spite of their magnitude in terms of absolute numbers, these migration

flows represented -except in the case of Paragua - less than 3% of the

population in the respective countries of origin. Uruguayan emigration

-mostly to Argentina- deserves separate consideration. During the 1970s it

reached an intensity equal to the mortality rate in the country of origin

(Fortuna and Niedworok, 1985). In Central America intra-regional

emigration is particularly significant in the cases of Nicaragua, El

Salvador and Guatemala.

Migration between the countries of the

English-speaking Caribbean Community is of a different nature. The

intensive circulation of people - eased by geographical conditions -

involves a relatively small percentage of changes of residence and a

higher percentage of recurrent movements (Simmons and Guengant, 1992),

some for a short period of time (with frequent returns home) and others by

stages, with stops along the way to the destination outside the

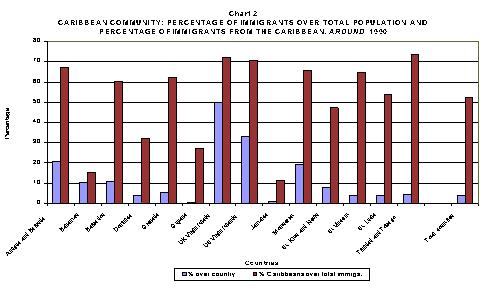

sub-region.5 Recent studies indicate that migration within the Community is

acquiring renewed dynamism, linked to higher standards of living and the

increase in the labour demand in some countries. It is estimated that

almost half of the immigrants registered in 1991 were from the same

sub-region, representing almost 4% of the total population in the

Community (Mills, 1997). In 1991 this situation varied greatly between

Caribbean countries. Most of the immigrants in Trinidad and Tobago, the US

Virgin Islands and Barbados - three of the five countries with the largest

immigrations stock - were from the sub-region, particularly in the case of

the U.S. Virgin Islands, where they represented one-third of the

population. On the other hand, immigrants in Jamaica and the Bahamas, the

other two countries with the highest stock of immigrants, were mostly from

countries from outside the sub-region (Chart 2). At the same time, the

majority of emigrants from Granada, Saint Vincent and the Grenadines and

Guyana entered the rest of the sub-region, preferably Trinidad and Tobago.

In the case of the first two countries, they represented almost a fifth of

the native population. These data highlight the enormous repercussions of

intra-regional migration on the demographic dynamics of Caribbean

Community countries (Thomas-Hope, 2000).

In the non-English

speaking Caribbean, one of the most constant migration flows is that of

Haitians to the Dominican Republic. In spite of occasional tensions, the

demarcation line between both countries has not been an obstacle to such

movements. Until the mid-20th century, substantial numbers of people

migrated from Haiti's highly populated and resources scarce North Eastern

region to areas beyond the international demarcation, with higher

productive capacities mostly in agriculture. Gradually, these flows became

seasonal movements dictated by crops' dynamics in the Northern and Western

regions of the Dominican Republic (Pellegrino, 2000).

Source: Mills

(1997)

4. Latin American

and Caribbean Nationals Residing Outside their Region.

During

the last decades, as immigration from overseas diminished and

intra-regional migrations stabilized, emigration to countries outside the

region have played a starring role. Even though the countries of

destination are many -there are increasing numbers of Latin American and

Caribbean nationals in Europe (mostly the United Kingdom, the Netherlands,

Spain and Italy), Asia (basically Japan) and Australia- the great majority

of emigrants from the region make their way to the USA and, to a lesser

extent, Canada.

Even though the emigration of people from the

region, mostly Mexico and Caribbean countries, to the U.S. is a phenomenon

of old - with fluctuations resulting from economic and social and

political developments as well as changes in the US immigration law -

recently it has increased considerably. Thus, the U.S. views migration

from Latin America and the Caribbean as a very relevant social phenomenon,

to the extent that the debate on its repercussions has become a priority

issue in its relations with the countries of the region (ECLAC, 2002).

Such migration contributes to increase the so-called "Latino" or

"Hispanic" population in the U.S., which according to the 2000 census has

reached 35.5 million. This group of immigrants and native Latinos

represents the largest ethnic minority in the U.S. (Grieco and Cassidy,

2001)

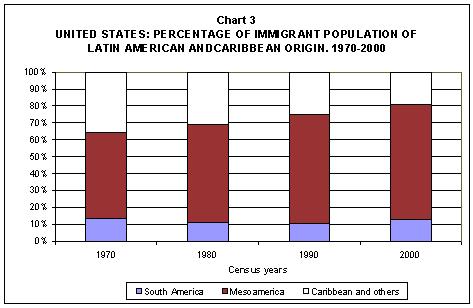

In the period between the 1980 and 1990 censuses the number

of Latin American and Caribbean nationals censed in the U.S. doubled,

reaching a total of almost 8.4 million, which represented 43% of the total

foreign population in the U.S. in the year 1990.6 This increase was accompanied by a diversification of the

countries of origin, as revealed by the immigration flows from Central and

South America (Chart 3 and Table 1). Thus, slightly more than half of the

above total of immigrants was from Mexico, one-fourth from Caribbean

countries (mostly Cuba, Jamaica and Dominican Republic) and the other

fourth from Central and South American nations, in equal percentages. Even

though Mexicans represented the largest number of immigrants -the 4

millions censed in 1990 doubled the 1980 total- during the 1980s people

from El Salvador comprised the fastest growing immigrants' stock (470,000

people in 1990). Their total number in the U.S. quintupled over a period

of ten years. During the same decade the number of immigrants from

Nicaragua and Guatemala more than tripled; from Honduras, Peru and Guyana

multiplied by 2.8; the number of immigrants from Haiti, Bolivia and

Paraguay doubled. The number of Cubans increased just slightly, however

the 740,000 Cuban immigrants represented the second largest group from

Latin America and the Caribbean and registered the highest percentage of

people who became U.S. citizens.

Source :IMILA Project,

CELADE. Data corresponding to the year 2000 was taken from the

Current

Population Survey.

| Table 1 | ||||||||

| UNITED STATES: POPULATION BORN IN LATIN AMERICAN | ||||||||

| AND CARIBBEAN COUNTRIES | ||||||||

| CENSED IN 1970, 1980 AND 1990 | ||||||||

| Region and country of birth | 1970 Population |

Relative distribution % | 1980 Population |

Relative distribution % | 1990 Population |

Relative distribution % | Annual growth

rate between censuses

(%) 1970-1980 1980-1990 | |

| TOTAL REGION | 1 725 408 | 100.0 | 4 383 000 | 100.0 | 8 370 802 | 100.0 | 8.7 | 6.3 |

| LATIN AMERICA | 1 636 159 | 94.8 | 3 893 746 | 88.8 | 7 573 843 | 90.5 | 8.2 | 6.4 |

| SOUTH AMERICA | 234 233 | 13.6 | 493 950 | 11.3 | 871 678 | 10.4 | 7.1 | 5.5 |

| Argentina | 44 803 | 2.6 | 68 887 | 1.6 | 77 986 | 0.9 | 4.2 | 1.2 |

| Bolivia | 6 872 | 0.4 | 14 468 | 0.3 | 29 043 | 0.3 | 7.1 | 6.7 |

| Brazil | 27 069 | 1.6 | 40 919 | 0.9 | 82 489 | 1.0 | 4.1 | 6.7 |

| Colombia | 63 538 | 3.7 | 143 508 | 3.3 | 286 124 | 3.4 | 7.7 | 6.6 |

| Chile | 15 393 | 0.9 | 35 127 | 0.8 | 50 322 | 0.6 | 7.8 | 3.6 |

| Ecuador | 36 663 | 2.1 | 86 128 | 2.0 | 143 314 | 1.7 | 8.1 | 5.0 |

| Paraguay | 1 792 | 0.1 | 2 858 | 0.1 | 4 776 | 0.1 | 4.6 | 5.0 |

| Peru | 21 663 | 1.3 | 55 496 | 1.3 | 144 199 | 1.7 | 8.8 | 8.9 |

| Uruguay | 5 092 | 0.3 | 13 278 | 0.3 | 18 211 | 0.2 | 8.9 | 3.1 |

| Venezuela | 11 348 | 0.7 | 33 281 | 0.8 | 35 214 | 0.4 | 9.8 | 0.6 |

| MESOAMERICA | 873 624 | 50.6 | 2 530 440 | 57.7 | 5 391 943 | 64.4 | 9.7 | 7.2 |

| Costa Rica | 16 691 | 1.0 | 29 639 | 0.7 | 39 438 | 0.5 | 5.6 | 2.8 |

| El Salvador | 15 717 | 0.9 | 94 447 | 2.2 | 465 433 | 5.6 | 14.3 | 13.3 |

| Guatemala | 17 356 | 1.0 | 63 073 | 1.4 | 225 739 | 2.7 | 11.4 | 11.3 |

| Honduras | 27 978 | 1.6 | 39 154 | 0.9 | 108 923 | 1.3 | 3.3 | 9.4 |

| Mexico | 759 711 | 44.0 | 2 199 221 | 50.2 | 4 298 014 | 51.3 | 9.7 | 6.5 |

| Nicaragua | 16 125 | 0.9 | 44 166 | 1.0 | 168 659 | 2.0 | 9.3 | 11.7 |

| Panama | 20 046 | 1.2 | 60 740 | 1.4 | 85 737 | 1.0 | 10.1 | 3.4 |

| CARIBBEAN AND OTHERS | 617 551 | 35.8 | 1 358 610 | 31.0 | 2 107 181 | 25.2 | 7.5 | 4.3 |

| Cuba | 439 048 | 25.4 | 607 814 | 13.9 | 736 971 | 8.8 | 3.2 | 1.9 |

| Barbados | - | - | 26 847 | 0.6 | 43 015 | 0.5 | 4.6 | |

| Guyana | - | - | 48 608 | 1.1 | 120 698 | 1.4 | 8.5 | |

| Haiti | 28 026 | 1.6 | 92 395 | 2.1 | 225 393 | 2.7 | 10.7 | 8.4 |

| Jamaica | 68 576 | 4.0 | 196 811 | 4.5 | 334 140 | 4.0 | 9.7 | 5.2 |

| Dominican Rep. | 61 228 | 3.5 | 169 147 | 3.9 | 347 858 | 4.2 | 9.4 | 6.9 |

| Trinidad and Tobago | 20 673 | 1.2 | 65 907 | 1.5 | 115 710 | 1.4 | 10.4 | 5.5 |

| Others | - | - | 151 081 | 3.4 | 183 396 | 2.2 | 1.9 | |

| Source: IMILA Project, CELADE. | ||||||||

The information

supplied by the U.S. Current Population Survey -a source that is subject

to sample-related errors and that is consulted to complement data from the

not yet available 2000 censuses- indicates that in the year 2000 the total

number of Latin American and Caribbean immigrants reached 14.5, from 13.1

million in 1997. These numbers represent a little over half the total

stock of immigrants in the U.S., thus between 1990 and 1997 the number of

immigrants from the region increased by 54% (Schmidley and Gibson, 1999)

and by 73% between 1990 and 2000 (Lollock, 2000). According to this

source, in the year 2000 the almost 8 million Mexicans represented 54% of

all Latin American and Caribbean immigrants in the U.S., followed by

Cubans, Dominicans and Salvadorians, with a little less than 1 million

each (www.census.gov). In some countries of the region, this increase in

Latin American and Caribbean emigration to the U.S. is counterbalanced by

a growing number of people returning home. For example, according to data

from the 2000 Mexican census, the stock of people born abroad reached

520,000 -50% more than in 1990- most of them below the age of 20 and born

in the U.S.

What is the number of immigrants from the region who

entered the USA illegally? The lack of appropriate data makes any

quantification of this phenomenon a matter of speculation. However, based

on past records gathered by the U.S. Immigration and Naturalization

Service we can estimate that in 1996 almost one fifth of the foreign

population (approximately 5 million people) comprised illegal immigrants,

with Mexicans representing 54% of the total, followed by people from El

Salvador and Guatemala (each with percentages below 10%) (INS,

2000).

Even though the limited information available does not allow

for accurate estimates, it is possible that in the year 2000 Latin

American and Caribbean emigration to countries outside the region other

than the U.S. reached a total of just over 2 million (Table A.2). Canada

is the major destination. In 1996 the number of immigrants from the region

increased to 525,000 from approximately 320,000 in 1986. Even though the

number of people from the Caribbean (mostly Jamaica, Guyana, Trinidad and

Haiti) represented half the total number of immigrants, people from

Central America (mostly El Salvador) comprised the fastest growing group.

In 1996, the total number of immigrants from this group grew to almost

70,000 from less than 19,000 in 1986.

Several European countries

have also received immigrants from Latin America and the Caribbean. The

highest numbers of immigrants from the region are in the United Kingdom,

the Netherlands, Spain and Italy. People born in the Caribbean Community

are an important minority in the UK, even though their number fell from

625,000 in 1980 to less than 500,000 in 1991 (data from OPCS Labour Force

Surveys and Census, quoted by Thomas-Hope, 2000)7. It is estimated that in the year 2000 the number of immigrants

from the region in the Netherlands reached 150,000, mostly from the

Netherlands Antilles (www.satline.cbc.nl). On the other hand, immigrants

to Spain are mostly from Latin America. In the year 2000 their number grew

to over 150,000 from 50,000 in 1981 (Palazón, 1996) (estimates based on

data from the migration regularization carried out recently in Spain,

www.mir.es).8 Similarly, a vast majority of the 116,000 immigrants from the

region living in Italy during the year 2000 were from Latin American

countries (www.istat.it).9 During the same year a little over 70,000 Latin American and

Caribbean nationals were censed in Australia (mostly Chileans,

www.immi.gov.au) and a similar number in Israel (mostly from Argentina,

www.cbs.gov.il). Finally, data from the Immigration Office of Japan's

Ministry of Justice (http://jim.jcic.or.jap/stat/stats/21MIG22.html)

indicates that in the year 2000 over 300,000 of the non-native residents

were from Latin America, more than 80% from Brazil and 14% from

Peru.

The analysis of regional emigration to such a vast number of

destinations requires that we take into account not only the impetus

originated by the migrant networks that began operating in several

European countries during the seventies, but also the fact that the

increase in migration flows was due also to the return of those who had

emigrated overseas and those who acquired the citizenship of the countries

of origin of their parents or ancestors (differed return). Similarly, it

is possible that a large number of the people born in Brazil and Peru who

are residing in Japan are descendants of Japanese immigrants (Nisei) who

had settled in those countries decades ago.

From a strictly

demographic point of view it is possible to argue that the evolution of

extra-regional migration reveals that the region has become a net exporter

of people. Yet, even though most of the countries of the region register a

negative migration balance and in several countries, particularly El

Salvador, Guatemala and Nicaragua this increased considerably during the

1970s, estimates for the region as a whole reveal much smaller numbers

(Villa and Martínez, 2001). Thus, during the 1980s the average net

(negative) migration rate for Latin America was only two over thousand.

National population estimates assume that such rate decreased gradually,

reaching a (negative) rate of one over thousand during the second five

years of the 1990s (CELADE, 1998).10

1 The free mobility of people is

limited to one region of the world (the European Union). It is also the

object of case by case negotiations within international agreements linked

to the temporary movement of people with skills required for specific

economic activities (or business or services) (ECLAC, 2002).

2 These estimates do not include

an unspecified number of people who migrate and work illegally or those

who move for short periods of time or participate in circular or return

movements (ECLAC, 2002).

3 In the non-Spanish speaking

Caribbean countries immigrants originate from the colonial powers of old

(UK, France and the Netherlands) and from India.

4 The use of inter-census

survivor relations by gender and age for the period 1980-1990 produced a

net immigration balance of 147,000 in Argentina and 60,000 in

Venezuela.

5 An

example of this is the Bahamas, which, besides receiving a large number of

immigrants seeking permanent residence is a transition stopover for many

people from other Caribbean countries, particularly Haiti.

6 The sharp increase in the

stock of Latin American and Caribbean nationals in the U.S. during the

1980s was due partly to the amnesty granted through the Migration Control

and Reform Law adopted by that country in 1986.

7 The flow of Caribbean

nationals to the UK was very strong until 1962, when that country decided

to end the free admission policy for Caribbean Community

nationals.

8 People

from Ecuador (29,000), Peru (28,000), the Dominican Republic (27,000),

Colombia (25,000), Argentina (19,000) and Cuba (17,000) represented the

bulk of this last group (

www.elpais.es).

9 The largest groups comprised

Peruvians (33,000), Brazilians (19,000), and Ecuadorians

(10,000).

10 These

rates are one-tenth below the natural growth rate of the population of the

region and represent a net annual loss of 560,000 people for the period

1980-1995 (CELADE, 1998).

http://www.sela.org/

sela@sela.org

SELA,

Permanent Secretariat

Torre Europa, Fourth floor, Urb. Campo Alegre, Av

Francisco de Miranda,

Caracas 1060- Venezuela

Tlf: (58) (212)

955.71.11 Fax: (58) (212) 951.52.92